TAASA Review Issues

January 1993

Vol: 2 Issue: 1

Editors: Heleanor Feltham & Christina Sumner

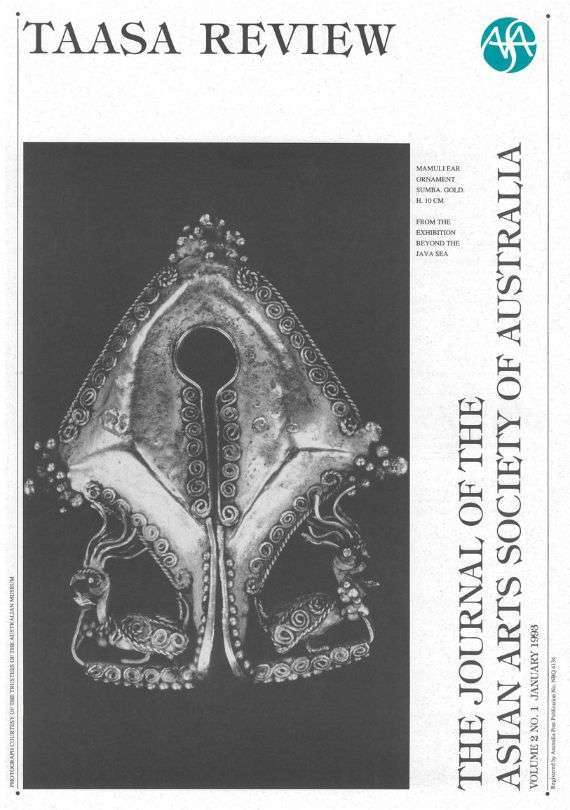

Cover Photo

Mamuli Ear Ornament

Sumba, Gold, H. 10cm

From the exhibition Beyond the Java Sea

TAASA Members may log in to download a PDF copy of this issue as well as past TAASA Review issues back to 1992.

Editorial

Heleanor Feltham

Welcome to our first edition of 1993. When we began The Asian Arts Society of Australia in October 1991 and decided that we would attempt to produce a well designed and hopefully substantial journal, we had nothing like the membership we needed to support such a quixotic gesture. What we did have was an excellent designer, access to beautiful paper, belief in ourselves and our society, and members who were willing to take the time to write excellent articles. We still have all of those resources – and enough members to not only sustain the journal, but to add their own contributions and individual style to a publication which, we hope, will continue to reflect the diverse interests of an expanding society.

On Human Rights Day, 10 December 1992, 1993 was declared the International Year for the World’s Indigenous People and should, according to Antoine Blanca, United Nations Coordinator for the Year, “provide an opportunity to focus the attention of the international community on one of the planet’s most neglected and vulnerable groups of people.”1 In the associated press release from the United Nations Information Centre, indigenous people are defined as “descendants of the original inhabitants of many lands, strikingly varied in their cultures, religions and patterns of social and economic organization. At least 5000 indigenous groups can be distinguished by linguistic and cultural differences and by geographical separation. Some are hunters and gatherers, while others live in cities and participate fully in the culture of their national society. But all indigenous peoples retain a strong sense of their distinct cultures, the most salient feature of which is a special relationship to the land.”2

It should prove a particularly interesting year for those fascinated by the arts of the indigenous and tribal peoples of Asia. One major exhibition Beyond the Java Sea: Art of Indonesia’s Outer Islands is due to open at the Australian Museum in March, while indigenous artists working in contemporary idiom will be represented at the Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art at the Queensland Art Gallery in September of this year. There will undoubtedly be other, minor, exhibitions of tribal arts, and opportunities for symposia such as our own, planned second Asian textile symposium in May. There will also be ongoing debate about the role and responsibilities of Western ethnographers, art critics and collectors in relation to indigenous peoples, and the development of arts in postcolonial societies, an issue central to the Biennale Conference last December.

According to United Nations sources, an estimated 300 million indigenous people live in more than 70 countries from the Arctic regions to the Amazon and Australia. China and India together have more than 150 million indigenous and tribal peoples. About 10 million live in Myanmar (Burma) while other large groups can be found throughout Southeast Asia.

Wherever they live, indigenous peoples tend to be marginalised, economically disadvantaged, often uprooted from their traditional lands and ways of life and forced to fit into prevailing national societies. Despite growing political mobilization in pursuit of their rights, they continue to lose their cultural identity along with their natural resources.

Moreover, “The high quality of indigenous artworks and cultural artefacts generates great demand for them, but theft and the unauthorized sale of indigenous items robs the creators of both money and their cultural patrimony. Thus indigenous peoples are looking to secure the right to their cultural property.”3

This necessarily includes the right to transmit or withhold skills, techniques, beliefs and knowledge, and one of the major issues today is the debate between the generic right to knowledge of human cultures and the right of individual cultures to self-interpretation. In the past we have had to be content to approach a culture through the sometimes distorting mirror of Western scholarship; now that it is becoming increasingly possible to do so, we can begin to listen to the voices of the people themselves.

Unfortunately today many indigenous cultures are increasingly threatened by their own local colonists, or by the developmental and other needs of the broader society of which they are a sometimes willing part. In some countries, for instance, access to education is limited to those professing acceptable beliefs. Education is essential to economic demarginalization and to the protection of rights, so the old gods and their ceremonies are put away, the ritual objects sold-off, and the mind-set that has for centuries produced a material culture layered with symbolism is lost. Oral transmission gives way to the written word, traditional life is lived with one eye on the tourist market, the young are no longer willing to spend the never cost-effective hours required for intricate artistry, nor do they see this intricacy as a participation in a spiritual formulation of the world around.

So increasingly “Indigenous peoples want to maintain their distinct cultures and transmit their cultural heritage to subsequent generations. Thus they are demanding the right to educate their children in their own languages, with their own textbooks and school material.”4

The United Nations draft declaration of 1991 highlights the “urgent need to promote and respect the rights and characteristics of indigenous peoples, which stem from their history, philosophy, cultures and socio-economic structures”. This does not mean encouraging cultural stasis or the creation of indigenous enclaves in the interests of tourism, rather the rights of peoples to determine for themselves their relationship to and degree of integration with other, more dominant, cultures.

As people interested in the multiplicity of Asian arts, and involved in the cultural debate, groups like ourselves need to maintain a sensitivity to our own involvement in the process of transformation – as tourists, collectors, researchers, presenters of culture -and to be aware of the rights of indigenous peoples to maintain, develop and control transmission of their distinct cultural identities.

“The Year was requested by indigenous organizations and is the result of their efforts to secure their cultural integrity and status into the twenty-first century. It aims above all to encourage a new relationship between States and indigenous peoples, and between the international community and indigenous peoples – a new partnership based on mutual respect and understanding.”5

1.United Nations Information Centre Press Release December 1992

2. Ibid

3. Ibid

4. Ibid

5. Ibid

Table of contents

4 READERS LETTERS

5 COMMENT – Carl Andrew

6 CHINA’S DUMB BELLS – Alan Dwight

8 PROFILE: DR. JOHN YU – Heleanor Feltham

9 FOILING THE FAKER – Julian Thompson

12 MANCHU SYMBOLS OF RANK – Judith and Ken Rutherford

14 THE WHIMSICALITY OF LEARNING CHEN HONGSHOU AND XU BING – Ian Dunn

16 CONFERENCE REPORTS

ASIA AND AUSTRALIA: KIND HEARTS AND CRITICS – Adrian Vickers

CONTEMPORARY ARTS: ASIA

A ROUNDTABLE AT THE ASIA SOCIETY NEW YORK – John Clark

18 IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN OBJECTS IN PUBLIC COLLECTIONS THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA: THE VERBIEST MAP – Tina Faulk

20 BOOKS

ART AND ASIAPACIFIC – Dinah Dysart

LIVING WOOD: SCULPTURAL TRADITIONS OF SOUTH INDIA – Jim Masselos

21 REVIEWS AND PREVIEWS Exhibitions, Lectures, Events and Performances

27 IDENTITIES RILEY KELLY LEE – Patricia Lee

28 MEMBERS DIARY – Jackie Menzies

BECOME A MEMBER

To download a PDF copy of this issue as well as past TAASA Review issues, receive discounted entry to industry events and participate in exclusive study groups, join the TAASA Community today.

TAASA Review Issues

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1996

1995

1994

1993

1992

TAASA Review Issues

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1996

1995

1994

1993

1992