TAASA Review Issues

June 2000

Vol: 9 Issue: 2

India-Popular

Editors: Ann MacArthur & Jim Masselos

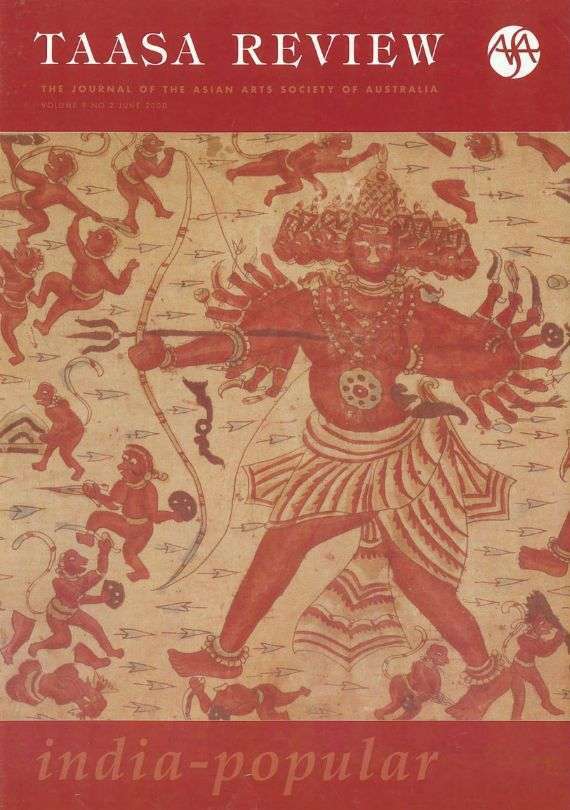

Cover Photo

India, Coromandel Coast, Painted textile with a scene from the Ramayana kept as a sacred heirloom doth in Sulawesi (detail), l 8th- l 9th century, handspun cotton with natural dyes and mordant, 93 x 462 cm, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Gift of Dr John Yu 1998.

TAASA Members may log in to download a PDF copy of this issue as well as past TAASA Review issues back to 1992.

Editorial

Jim Masselos

The idea behind this issue is simple: to capture a flavour of the popular in the art of the Indian subcontinent. It is not a comprehensive overview of all the forms which the popular has assumed in the region or of the various works in each form. This then is a soupçon, a tasting, rather than a full banquet.

I have used the word, popular in order to escape aesthetic judgments inherent in notions of a hierarchy of art forms. I wanted to avoid any connotation of a qualitative difference between ‘high’ and popular art, between ‘fine’ art and craft, between religious and secular art, or folk and elite art. In the Indian context distinctions transferred from European theoretics are difficult to apply, if at all applicable. Each category has its own artistic validity. None is innately superior or inferior.

As is to be expected the audience features strongly in these articles, but what emerges is that form is universally popular. The popular need not encompass everybody, even if it appeals to large numbers of people as with theatre and cinema. The amulets described by Joan Bowers derived from the needs of particular Hindu pilgrims while the clay horses at the tomb in Lahore fulfil, as Farida Batool notes, specific devotional purposes. Even the early photographs in my study provided momentos for another grouping, the ruling class of the day, the British rulers, while Roy Dalgarno’s re-figuring of Indian subjects became part of carefully targeted big business promotions.

In the case of tribal art and the art of peasant women, John Kirkman shows how their audience has moved beyond the communities which used these works for ritual and daily needs outwards to incorporate a wider constituency. Neeti Bose studies entrepreneurs who promote an art increasingly geared to the aesthetic and decorative needs of outside groups within and beyond India. Here the kind of subject matter, the extent of detail, and the degree of elaboration of technique are all subject to negotiation and constitute a collaboration between artist and buyer that goes beyond mere purchase.

Another striking point the papers collectively establish is the role of the new. Whether it be the poster art which Kajri Jain discusses or the proscenium-derived theatre presented by Kathryn Hansen or Safina Uberoi’s montage of the mass cinema all incorporated new technologies to create something that is totally of the subcontinent, subcontinental in its feel, unique in its quality and content. Satyajit Ray put his finger on it when he spoke about Asian cinema and the ‘existence of an art form, western in origin but transplanted and taking roots in a new soil… the tools are the same but the methods and attitudes… are distinct and indigenous’ (cited in the Statesman Weekly [Calcutta], 1 Apr. 2000, p.12). So, too, with other global media on the subcontinent which maintain regional and national characteristics.

The popular arts of the subcontinent have vigour and energy – and an immediacy that can be overwhelming. They are punchy and vital because they satisfy an audience that has definite ideas about what it wants. They also meet less clearly articulated needs that derive from a long past, and which refer to sets of customs, traditions, or religious patterns. But they also meet new needs, even if within the constraints of discourses which attenuate back in time. They achieve this through incorporating anything useful that is available, whether from within or outside India. In this sense, the popular art of the past two centuries is no different from earlier Indian art – which was always quick to absorb new influences, techniques and mediums and create something different; whether in the form of the Buddha figure or miniature painting on new kinds of paper. Popular art in the subcontinent does not imply unchanging tradition as associated terms like folk art or crafts might suggest, what it does denote is adaptability, yet it is change that is contained in, and expressed through, prevailing subcontinental discourses. It is the creativity of the subcontinent which this popular art expresses and equally its ability to refashion itself. It represents something that is new even while parts may appear derivative. The popular has a freshness in its gaze and one constantly refreshed.

Table of contents

3 EDITORIAL: INDIA – POPULAR – Jim Masselos

4 INDIAN ‘CALENDAR ART’ AND THE TIME AND SPACE OF THE POPULAR – Kajri Jain

6 TRADITIONS IN TRANSFORMATION: TRIBAL ARTS AND COMMERCIALISATION – Neeti Sethi Bose

8 STIRRING THE POT – John Kirkman

10 POPULAR THEATRE IN NORTH INDIA – Kathryn Hansen

12 REPRESENTING THE FIGURE: CONTEMPORARY POPULAR CULTURE IN PAKISTAN – Farida Batool

14 BEATO’S DELHI: THEN AND NOW – Jim Masselos

16 IDENTITIES – ROY DALGARNO

17 COLLECTOR’S CHOICE – Joan Bowers

20 A LITTLE BIT OF BOLLYWOOD – Safina Uberoi

22 ‘BETTER THAN A WEDDING OR A FUNERAL!’ A LONG LIFE: RESTORATION OF THE SEE POY FAMILY PORTRAITS – Jacqueline Macnaughtan

24 OBITUARY – ANNE BAKER

24 TAASA MEMBERS DIARY

25 REVIEWS AND PREVIEWS

BECOME A MEMBER

To download a PDF copy of this issue as well as past TAASA Review issues, receive discounted entry to industry events and participate in exclusive study groups, join the TAASA Community today.

TAASA Review Issues

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1996

1995

1994

1993

1992

TAASA Review Issues

2025

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1996

1995

1994

1993

1992